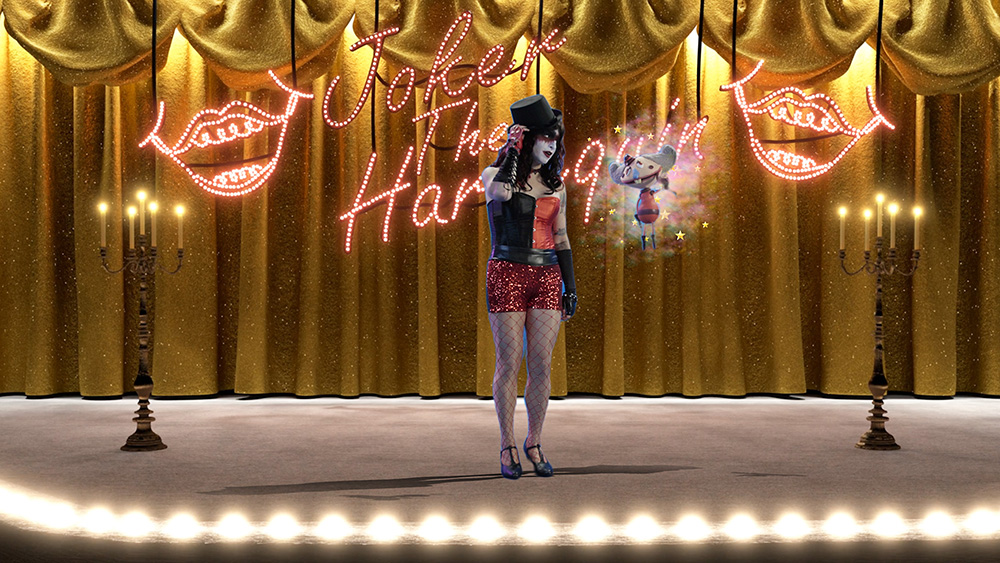

THE PEOPLE’S JOKER – by writer-director-star Vera Drew drawing on her life experiences – is a deeply personal journey that’s as much documentary as it is parody. It’s a re-imagining of the classic coming-of-age autobiographical story about an unconfident, closeted trans girl as she moves to Gotham City to make it big as a comedian by joining the cast of UCB Live, a government-sanctioned late-night sketch show in a world where comedy has been outlawed.

Mad Joker (Vera Drew)

Mainstream success is elusive. So, she unites with a motley crew of strivers dealing with rejection and meets a promising significant other named Mister J. “Joker the Harlequin” is born again as a confident (and psychotic) joker on a collision course with the city’s fascist caped crusader.

Vats of feminizing chemicals, sexy cartoon interludes, scarecrow psychiatrists, CGI Lorne Michaels, and psychedelic gender dysphoria all play supporting roles.

THE PEOPLE’S JOKER features a superhero-sized cast of celebrated comedic talent in both voice and live action roles behind the kaleidoscope of characters that lampoon the iconic heroes and villains of the DC comics’ world.

It features cameos from comedy multi-hyphenate Tim Heidecker, award-winning actor Bob Odenkirk, Maria Bamford (Netflix’s Big Mouth, Adult Swim’s Teenage Euthanasia), and Scott Aukerman (Between Two Ferns with Zach Galifianakis co-creator and host of the Comedy Bang! Bang! podcast), with Vera Drew, Lynn Downey (Amazon Prime Video’s Daisy Jones & The Six), Nathan Faustyn (SADDLED), and Kane Distler, in his film debut as Mister J.

Cartoon Fight (Nathan Faustyn, Kane Distler, Daniella Baker, Vera Drew)

THE PEOPLE’S JOKER is in no way created by, endorsed by, or affiliated with DC Comics or any of its related companies.

*Please note:

Vera Drew’s pronouns are she/her. In this film, Joker’s pronouns are also she/her.

When writing about or discussing the character Joker, she/her pronouns are always correct, whether she’s a child, a drag queen, etc. In the film, the characters misgender and dead-name Joker, but that is a creative choice. In any articles and reviews, the main character of this film should be referred to by the name of Joker and with she/her pronouns.

Vera Drew’s Director Statement

You’ve heard some version of it before: “2020 was gonna be the year but then March rolled around and … well, you know.”

What is my pre-vax-Covid-I-was-gonna? Well, that was supposed to be the year that I climbed out of the dank shadows of an alt-comedy editing bay and used what I learned from my 10+ years of production experience to finally begin my career as an episodic television director.

Of course, when business shutdowns started, so did the entire TV industry — especially my little corner of it. In addition to the dread of widespread viral infection, impending social upheaval, and never getting paid to make comedy again, I couldn’t get work as an editor (it was to be expected — adding fart sound effects to Tim Heidecker’s eyes blinking isn’t quite what I would call “essential work”).

On the first day we were all told to stay home, an even deeper fear settled in for me … what if I never get to make a film now?

It probably sounds selfish, but please understand: I knew I was a director before I knew I was a girl. At six years old, I remember watching BACK TO THE FUTURE on VHS for the 5000th time and realizing I wanted to do … that. I didn’t even know what filmmaking was or how a movie came into existence, and yet I knew in my bones that I was supposed to make movies.

But there I was in March 2020. I still hadn’t made a movie.

If you had looked at my IMDb, you may think my angst was unwarranted. My first gig in Hollywood was line-editing the first A24 movie: Roman Coppola’s A GLIMCPSE INSIDE THE MIND OF CHARLES SWAN III. On my first day on set, I smoked a cigarette with Charlie Sheen. It was a really cool first job for a dumb stoner from the Midwest.

My next job was as an intern on season one of “The Eric Andre Show,” followed by camera assistant on season one of “Nathan For You.” I went on to edit three seasons of “Comedy Bang! Bang!” and one of “Check It Out With Dr. Steve Brule.” I am the transexual Forest Gump of Alternative Comedy Post Production™, Emmy nominated for her work on Sacha Baron Cohen’s “Who Is America.”

I am thankful that I got to work on a lot of cool shit and learn my craft under the employ and mentorship of literal comedic geniuses, but when that pandemic hit, I felt like where I had devoted my energy —my entire career— had been a total and complete waste of time.

I was scared I had let comedy distract me from becoming the type of filmmaker, and quite possibly, the type of person I was supposed to be. Coming out in comedy TV was hard, always surrounded by often well intention but ultimately clueless cis boys obsessed with meta humor. Long before coming out, I often used my own art to express my queerness, but I often did it in a monstrously and toxically feminine way.

When I wasn’t spending all night editing Dick Chaney footage with Borat looming over me in basketball shorts, I spent the bulk of my free time in my 20s at a public access station (aka an abandoned warehouse) that I started with my friend, filming “sketches” that were more like video art fetish videos. While my drag routines and self-deprecating comedy shtick were an expression of my identity, this community saved my life, even if sometimes it was just self-harm with dick jokes.

As society crumbled outside, in my fearful and probably manic state I started writing a script for a horror comedy about an annoying drag queen that is physically addicted to irony and gets sucked into a goddess worship cult. It was also right around that time that the guy who directed JOKER said something really stupid …

“Go try to be funny nowadays with this woke culture,” he says. “There were articles written about why comedies don’t work anymore — I’ll tell you why, because all the fucking funny guys are like, ‘Fuck this shit, because I don’t want to offend you.’ It’s hard to argue with 30 million people on Twitter. You just can’t do it, right? So you just go, ‘I’m out.’” – Todd Phillips, Vanity Fair.

Joker on the Staris (Vera Drew)

My friend Bri LeRose (who wrote on “Lady Dynamite” and “Arrested Development”) saw this quote and felt inspired to tweet: “I will only watch this coward’s joker movie if Vera Drew re-edits it.” So I replied, “Sure.” She Venmo-ed me 12 bucks. I was jobless and mentally ill at the time, what else was I going to do?

I began actually re-editing JOKER 2019. It was supposed to be a few fart sound effects and some silly rhythmic glitch editing —think Everything Is Terrible meets Negativeland— but then I got inspired. As I watched the movie over and over and over again, earnestly trying to edit my found footage experimental Joker remix, I reconnected with my childhood love of Batman and recalled an early memory of realizing I was transgender.

It was 1995, the same year I realized I was a director. My dad and uncle took me to see my first PG-13 movie: Joel Schumacher’s big-budget gay art film, BATMAN FOREVER. That scene came up where Nicole Kidman’s character is waiting for Batman in her nightie.

I remember sitting there, as a six-year-old boy, deeply confused. Why did I feel represented by her? Why did I want to look like her? Why did I want someone to look at me the way Batman looks at her? The rubber nipples … That day was one of the many breadcrumbs in realizing that I was trans, and May 2020 was when I realized how important and foundational these characters have always been for my queer identity.

Perhaps that propaganda we’re fed every time someone says something critical of Marvel or DC films is true — these characters are our modern myths. Myth is about coming of age. Myth belongs to the people.

I went back to Bri and said, “You got me into this mess and now I need you to help me write a screenplay for a trans Joker parody.” And Bri said, “Sure.” We took the core elements from my original drag queen horror idea and began writing a deeply autobiographical coming-of-age story. Despite his bro-y union-busting politics, Todd had made a film that accurately portrayed class struggle, what it is like trying to get healthcare, and how much the system is keeping everyone trapped in a cycle of abuse.

As a trans chick living in the States, the themes of his film resonated with me. Outside of 2016’s SUICIDE SQUAD, my main sources of inspiration weren’t even comic book related, consisting of RETURN TO OZ, HEDWIG AND THE ANGRY INCH, BOYHOOD AND GOODFELLAS to name a few.

We started the screenwriting process as two friends who kinda knew each other and, in collaborating, we opened up and processed a lot about both of our lives together: Growing up queer and closeted in the Midwest, our moms, working in comedy showbiz — and a shit ton of trauma. Bri doesn’t watch superhero movies, and I watch too many.

I was the one urging Bri to write impossible-to-film-on-an-indie-budget superhero set pieces around a one-woman-show-style narration, and Bri was the one encouraging me to write honestly and tenderly about what it was like coming out of an abusive relationship. For me, this film was very expensive therapy. It helped me come to grips with the fact that queer people can hurt each other and that, sometimes, the first person you love—that first person who loves you unconditionally, whose love finally melts your sketch-comedy-poisoned heart and find the real you inside — that person isn’t always supposed to be in your life forever.

The process of completing this film changed everything for me. I was finally making the art that I was supposed to be making, and it didn’t matter that it took me 30 years to finally make a movie. Because there I was, making a movie that only I could make— and I was making it with my friends. I was mythologizing my life with a team of the most talented artists alive. I was making the film that I needed when I was an alienated 12-year-old queer kid growing up in my own midwestern Smallville. A film that LGBTQ+ kids like that still need (even in 2024). A film for anyone who ever had the courage to live authentically in a synthetic world created by hypocrites.

In the past year since unleashing the film, life has imitated the art that I made to imitate and understand my life. Making movies is magic. Enjoy THE PEOPLE’S JOKER. It saved me.

I used to make and host a web series called “Hot Topics with Vera Drew,” which is the only web series with the expressed purpose of getting Vera Drew sponsored by Hot Topic

It was all a ploy to get Hot Topic to sponsor me and fund the high school emo-girl phase that I never got to have since I was closeted as a teen. It was the entire premise of the series. Hot Topic never sponsored me (I am too edgy for them), but it was on that series that I first announced what Bri and I were doing and where I opened up the creative process to any artists, musicians, and filmmakers who wanted to help us realize our vision.

Joker Dancing (Vera Drew)

I didn’t expect that many people to respond to what I thought was a niche idea, but literally hundreds of people —many gay and/or trans— jumped at the chance to work on this film. Animators, illustrators, editors, a lot of lawyers—a small community of people, many of whom never had aspirations of film before, came together to make The People’s Joker.

Our script was ambitious and, when we finished it, we had no idea how we were going to pull a lot of it off. As that community formed, necessity became the mother of invention, and I used my experience producing, editing, and VFX-ing low-budget comedy television to bring all of these artists’ disparate styles together into a vibrant and weird mixed-media aesthetic.

I can’t tell you how cool it is to wake up to an email from someone asking, “How does our batmobile look? Does it look too much like a penis?” (my response, of course, being, “Make it look more like a penis”). I had a vision for this film, but I knew I had to trust the talent and vision that everyone else was bringing to the film. It was always going to be my story on the screen — with my face in almost every single scene— so being surrounded by a community both very creative and queer (finally!) for the first time in my life, it was easy to put my ego aside and relay the core idea of what I had in mind to my collaborators, and encourage them to run wild with it. The results were a very organic, go-with-the-flow-and-adapt creative process.

The film’s mixed-media aesthetic and machine gun-paced joke delivery allowed us to employ a lot of different styles with our versions of ‘happy mistakes.’ When 3D animator James Moor made our first test render of Lorne Michaels’ death sequence, there was a glitch that ripped the texture off the 3D model’s body and made it look like his clothes were flying off in a wind tunnel. We decided to keep it in.

Joker and Mx Mxyzptlk (Vera Drew and Ember Knight)

When I asked AT Pratt to make our broken-down amusement park matte painting, what I got back was a huge piece of psychedelic art with an Escher-like perspective that I had no idea how we were going to ever use as a background. If this were a TV show I was working on and we received materials like this, someone would have sent the art back and said “it’s wrong—fix it” but, in our case, with the help of our extended team, we were able to make everything fit together.

When Trevor Drinkwater (who plays the Riddler) said that he wrote a whole backstory for his character about streaming wars and tech snobs, I decided to write it all into the script. In the film, we talk about the improv concept of “yes and.” My creative process on this film was Yes And-ing every absolutely bonkers and beautiful artistic choice pitched to me by our team. No first-time filmmaker has ever been so lucky.

We shot the live-action portions of the film in five days at Tim and Eric’s office. Nobody ever believes that but it’s true. After that, the film took me another year and a half to finish. If you had told me how hard it was going to be to finish this, I would have never done it. It turns out no amount of green screen removal experience can prepare a girl for what it is like to have every single shot of her debut feature be a visual-effects shot.

It was grueling and there were times when I questioned if we’d ever finish it. It was with the help of my producer, Joey Lyons, that I was ever able to manage such a large team of people and such a tight turnaround for our initial film festival deadlines. It was a labor of love made by a lot of people who love each other. It was all worth it.

{Click here to return to Part 1}

Publisher, Editor Gregg W. Morris