Director Rudy Valdez.

THE SILENCE screened at the New York Latino Film Festival August 23, and the Q&A with Director Rudy Valdez and Moderator Calixto Chinchilla, Founder/Executive Director of the festival, was riveting. Film reviews of THE SILENCE are embargoed until October 15 when it debuts on HBO – no embargo for this Q&A article.

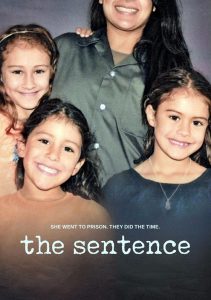

THE SILENCE won the 2018 Sundance Audience Award. Valdez explores the devastating consequences of mass incarceration and mandatory minimum drug sentencing by telling the story of Cindy Shank, his sister, a mother of three young girls as well as families and relatives – and his experiences. The film was 10 years in the making.

Cindy Shank was sentenced to 15 years by a federal judge for her tangential involvement in a Michigan drug ring years. Regarding her tangentiality, she was the girlfriend of a Lansing Michigan drug dealer who ran his business out of their home. Though she was not directly involved in the criminal activity, she was there when things went down. She didn’t drop a dime on him, never turned him in. However, she eventually left him and started raising a family with her new husband and things were going well until the feds knocked on their door several years later.

At the NYLFF Q&A, Valdez talked about the 10 years of his up front and personal, imaginatively creative, fly-on-the-wall documentation of the literally day-to-day life of his mom and dad and other relatives, as well as Cindy’s three young daughters and her husband living in the wake of her incarceration as they seek her freedom. This is reality filmmaking at its best.

The Q&A has been edited for style and length.

NYLFF Founder Calixto Chinchilla.

The heart of the Q&A, before it was opened up to the audience, began with NYLFF founder and Executive Director Calixto Chinchilla’s question to Valdez: “How is Cindy doing?”

At first Valdez replied, “She’s doing well. She’s has a good job. She’s making a living and she’s being a mom.” But then he added, “The real answer is, I don’t know because I don’t think we’re going to see the ramifications of all this for another five or 10 years.I think her and her daughters have gone through something that so few people have. And the girls, through the hardest years of their life, they did it [growing up} without their mother.

“And they have a natural distrust of systems in general. Soon they’re going to be joining the education system and the healthcare system. They have this anxiety about that, and I think we’ll get to the real ramifications and how this truly affects them later on.”

Calixto Chinchilla: “So how is she adjusting?” Valdez said, “I was never concerned about her. in that, I never worried about her finding a job or what was going to happen. I knew that she wasn’t going to let anything stand in her way. One of the bigger reasons why I fought for Cindy and why I fight for so many people like her is that she is deserving of a second chance.”

“I knew that she would take every opportunity in front of her. And one of the reasons why I believe she was granted clemency was because, when you read her petition, when you read what she’s done with her life prior to going away during her time incarcerated, she took every single opportunity to make sure that she was the best person that she could be, that she deserved that second chance.”

Calixto Chinchilla: So how are the girls readjusting?” Valdez replies, “That was a big adjustment, actually. Especially the two youngest ones. They went their entire life without Cindy there. They spent nine and a half years without mom there, and then all of the sudden this other parent is home. She wants to discipline. She wants to mother. She wants to set parameters. It was a tough adjustment, at first, I think mostly for Autumn, the oldest.”

“She pushed back a little bit when Cindy first came home. So to Cindy’s credit, Cindy didn’t push. She said, ‘When you’re ready, I’m here and I’m going to be here.’ And Autumn just needed space. Eventually, she came back and I feel like they’re closer than they ever have been. There’s always the disconnection between Cindy and Autumn, from birth. But they’ve always had this really special connection, and that went away a little bit when Cindy came home. But I think they’re finding their way back to it.”

“And I think of the two, Annalis, who – I don’t know if it comes across on camera – but she is a maniac. She is, in a good way, in the greatest way, she’s just a ball of energy. She didn’t always know how to focus that because she constantly had this frustration with her mom being away. I think she’s finally focusing into finally coming into her own, and it’s been amazing to see how this thing that can be such a challenge has really helped them evolve as people, as a family. They’re really pushing through it and making the best of it.”

“It’s literally such a dream come true to watch it. Or to call Cindy every now and then. She’ll answer the phone and say, ‘I can’t talk, I’m on my way to Anna’s soccer game.’ I almost cry, I’m an emotional basket case. I cry almost every time because I know how different it could be if things didn’t happen the way they did. We try to not look back, and move forward and take advantage of every opportunity now.”

Calixto Chinchilla: “You’re putting the camera on your family. At what point did you say you want to put it down? At what point do you say, This is too much for me? And how do you document your family going through everything, and keep going? At what point, it’s really hard to disconnect. It’s different if the subject is not related to you, but you’re seeing your nieces, you’re seeing your sister going through this. You’re seeing the babies’ father going through this. At what point do you say, put the camera down?”

Says Valdez: “The very first scene in this film is the moment, literally captured on film, when I became a filmmaker and when this became a film. I started this film not as a documentary but just as a way to capture moments for my sister who was going to be away. We were looking at 15 years at the time.”

“Pictures are amazing and phone calls are wonderful [Cindy called home frequently from prison], but I needed her to see them live. I wanted her to see them cry. I wanted her to see them run and grow and play and dance and fight.”

“I needed her, one day, to be able to watch them grow up. That’s how this started. And then, I flew back because Autumn was having her first dance recital. Completely organically, completely unexpectedly, Cindy calls. And you see it in the film, and she says that line, ‘You know what Mommy’s going to do when you go to dance? I’m going to lay down in my bed, I’m going to close my eyes, and I’m going to think about you.’

It was that moment that I realized that I had an opportunity to tell a story that you don’t get to see: The people left behind, the children who are doing these sentences, the families left behind. And I knew that I needed to figure out how to tell that story. It was difficult, and I didn’t know what I was doing, clearly, when you look at the footage at the beginning. I had no idea, I’m chasing the story. The next sort of moment where I feel like I truly owned it was the first time I was filming my father when he was crying.”

Picture courtesy of NYLFF

“He breaks down in front of me, and everything in my heart. I was telling this to somebody earlier. Everything in my heart, everything in my soul was saying, Rudy, don’t be an asshole. Put down the camera. Hug your father. Tell him it’s going to be okay. Tell him you’re going to make it through this.”

“And then something else came over me. It was literally this [inaudible] and it said, Rudy, hold your shot. This is for the greater good. When you told your family you were going to make a documentary about this, you promised them that one day, you were going to make something good. You were not going to let this be in vain. You were going to make something good.”

“So it took over and I had to – I talk about it a little bit in the film – it became this defense mechanism for me. It became this barrier for me, where I had to stop thinking about it emotionally half the time, and I needed to separate. I would literally, when things were getting emotional, I would start saying in my head, Do I have enough battery for this film? Am I focusing? Hold your shot. Hold your shot. Hold your shot. How much time do I have on the cards?”

“I started going into the technical aspect in my brain, in order to disassociate myself from what was happening emotionally.”

End of Part 1

Gregg W. Morris can be reached at gmorris@hunter.cuny.edu