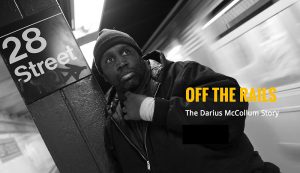

Pictures courtesy of Adam Irving

Adam Irving, researching ideas several years for his first full length documentary, was reading a Wikipedia article about people obsessed with trains and came across a Wikipedia article about Darius McCollum’s. “‘Darius McCollum has spent more than half his adult life in prison for impersonating New York City transit workers,'” he recalls the first line of the article, “‘and he has Asperger’s syndrome.’ And I thought, wow, that’s a fascinating story, I hope no one’s done a movie about this guy.”

Said Irving, “I was just drawn to the imposter aspect of it, someone who could pretend to be another person hundreds of times for years, and who’s spent decades in prison, never hurting anyone.”

Darius’s news portfolio of misdemeanors started when he was first arrested in his teens after commandeering a MTA subway train, operating it without a hitch like a licensed pro for several stops – imaginatively depicted early in OFF THE RAILS.

That his portfolio increased through the years as he was re-arrested for commandeering more subway trains as well as buses, his sentences becoming stiffer because of repeated parole violations. He was on a track for harsh penalties as he was moving from youth to teenager to adult recidivist. None of his stories were ever of the genus if it bleeds, it leads but his misdemeanors fitted right in with Big Apple folklore. Nevertheless, he couldn’t end his journey of self-destruction – Asperger wouldn’t let him.

The young, Queens-born subway savant about the workings of the New York City mass transit system – imaginatively depicted in the film – was made out to be kooky and weird in new stories. The accounts about his misdemeanor capers, however, did improve slightly in tone after a New York Times article reported that he had Asperger’s Syndrome, a mental disorder that started in childhood.  Those with the disorder can have significant problems interacting with people and dealing with social situations and may engage in repetitive patterns of behavior. Symptoms usually begin before two years old and typically last for a person’s entire life. It may be partly inherited and environmental factors may also play a role.

Those with the disorder can have significant problems interacting with people and dealing with social situations and may engage in repetitive patterns of behavior. Symptoms usually begin before two years old and typically last for a person’s entire life. It may be partly inherited and environmental factors may also play a role.

There aren’t any headlining, 6 O’clock crimes stories, with a mental illness angle, this writer can recall in recent memory about someone with Asperger’s Syndrome. Paranoid schizophrenia, yes, and a tabloid favorites, sociopathy, psychopathy, yes, but not Asperger’s.

“I love stories about New York” says Iriving, “and I’ve actually taken the subway in 51 cities around the world, so I’m a bit of a subway buff myself – not nearly the level that Darius is. I lived in New York for a couple years when I was in grad school at NYU and I took the subway every day, so the idea that the person who’s driving could have been an impostor was fascinating.”

Irving is a film maker, an artist, not a journalist but his technique for producing OFF THE RAILS has to awe consummate journalists and news media aficionados – and, perhaps, even private detectives and gumshoes. The film is one big gem of incredible visual story telling but he also has a meticulous approach to gathering information and persuading people to let him interview them. His pursuit of truth can easily match the pursuit of any Pulitzer Prize winner in recent memory on the hunt breath taking stories.

His Q-ing & A-ing prosecutors, lawyers, counselors and others he considered important for his film are sublime. “I think that a lot of documentaries fall short because they’re relying on interviews to tell the story, and the problem is they don’t have really good interviews” he says. “They get scientists, and engineers, and politicians who maybe are very smart and good at what they do, but they’re not good at speaking on camera.”

“With Darius’ story, I did interview some people who never made it in the film, and one of the reasons is, to be honest, they weren’t very compelling. They weren’t open, they weren’t emotional. So, what you’re seeing on screen are the people who gave the best interviews, and within their interviews, you’re seeing the best bits. That’s the beauty of editing,” says Irving who did the editing for his film.

“The other thing is people who like Darius, who have helped him, who are drawn to him, they love talking about him because they want to help him and they think he’s interesting, and they’re just as fascinated by his story as I am, so they speak about him with the same kind of passion that I do, so that’s why it was actually fairly easy to find good interview subjects.”

Jude Domski was one of his first contacts. He flew to New York in fall 2012 to meet with her. Domski wrote an award winning play about Darius, Boy Steals Trains, “a shaming collective finger at a judiciary that refuses to recognize Darius’s condition, according to a Wikipedia article about one of its theme.s The story was also made into a BBC radio play, broadcast on BBC Radio 4 several years ago.

“And she told me how to get in touch with him. Over the next six months I exchanged over 100 letters in the mail with Darius, getting to know him, and then I eventually went to New York and I visited him at Rikers, and the rest is history.”

History is still in the making. OFF THE RAILS was a grand jury award winner for NYC DOC’s Metropolis Competition and the film has been a sold-out feature at the Metrograph theater where it’s run originally was planned for November 18 to November 24 but has been extended to December 1. It’s been playing before sold out audiences. It’s Facebook page also reported November 22, that it was still in the running for an Oscar shortlist for Best Documentary.

Irving flew to North Carolina to interview Darius’ mom. “At first, his mom was tough to get a hold of because of her age, and it was just hard to get her on the phone. She would rarely answer the phone,” says Irving. “But once I flew down to North Carolina and I met her in person, and she saw that I was just a nice kid, she was willing to talk to me. She just really couldn’t differentiate me from the 20 other journalists that have interviewed her.”

It took him a few months to clarify for her that he was doing “a documentary, a movie, a multi-year project,” that it wasn’t going to be “some half a page tabloid story” mocking her son or his family. Darius, however, was on board from the beginning. “He loves attention, he loves getting in the news, and he not only likes being on camera, but he was interested just the same way he was interested in trains, he was interested in filmmaking,” Irving says.

“Most of the days we were shooting were in the winter of 2013 getting into ’14, which was one of the coldest winters in New York history, and it was brutal,” he recalls. “There were some days, it was so cold where we could only film outside for about 10 or 12 minutes, and then we’d have to go in and warm up, and then go out again, because the tips of our noses and ears would freeze.”

The stress was relentless. “It was the combination of the weather, having long shooting days, and knowing at any moment that Darius could get tempted and go and take a train or a bus, and then I wouldn’t be able to film him for five years. So, there was that high stakes, high pressure, like, we need to get everything we can in 10 or 20 days, and then wrap it.”

There were times when Darius could be uncommunicative, such as “he wouldn’t answer in the way that was very helpful. Maybe his energy was low, or he mumbled, or he just didn’t answer the question, and I’d say, ‘oh, can you answer I again this way?’ And he’d say, “No, I already did it three times. There were times when he just flat out refused and I just accepted it, and there were other times where I would just have to beg him and say, ‘The movie, I promise you, will be so much better if you can just answer tell this story one more time with a little bit more energy.'”

“When you have an actor and you’re paying them, they’ll just do whatever you want because that’s their job, right? They’re being paid to stand here at this time, at this spot, and say this line, and if you want them to say the lines 30 times, they’ll say it 30 times. In documentaries, you have to be more respectful because you’re not paying someone to act for you.”

“He would persevere, and he would give in, and he would do it so much better, and he would see how much better the shot was, or the line was. He learned that it was worth, for him, putting in the effort.”

Gregg Morris can be reached at gmorris@hunter.cuny.edu