Article By Senior Editor and Special Correspondent James Kelly

Pictures by James Kelly

May 13, 2017

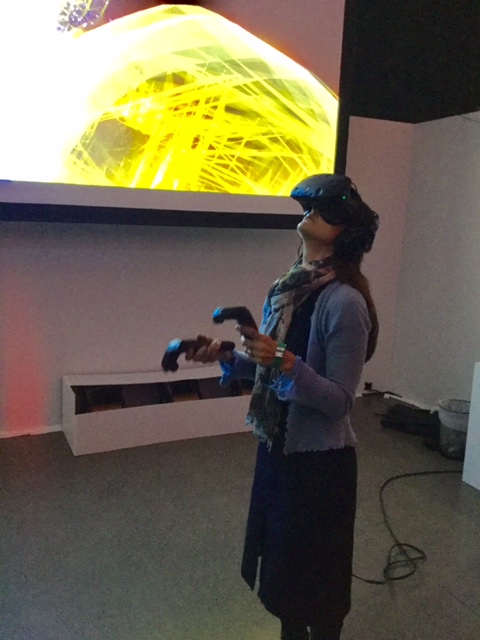

The Tribeca Games Festival was a spectacular two-day fête April 28th and 29th, the last two days of the festival. The first night featured a kick-off party that gave patrons a chance to network and play some of the most talked about unreleased games, like the first-person, action-adventure game Prey and the action role-playing game, Nier: Automata.

Patrons took part in a “crowd-play” of the new Guardians of the Galaxy: vol.2, allowing them to choose how the story unfolded by voting on their phones. The last half of the first night featured a performance by Guernsey born DJ, Alex Cross, otherwise known as Mura Masa.

The second night was what the festival was all about, featuring staged interviews and discussions with well-known names in the gaming industry, like Hideo Kojima and Ken Levine, as well as representatives from up-and-coming game developers.

The overarching theme of each conversation was how the gaming industry compares and contrasts to the film industry. There were six interviews and panel discussions with representatives from the makers of Firewatch, Overwatch, Halo, Max Payne, Metal Gear Solid, and Bioshock.

Halfway through the discussions, Jane Rosenthal, a co-founder of the Tribeca Film Festival, introduced the game-makers who were to follow and to thank contributors who made the festival possible. In her address, Rosenthal expressed the importance of story-telling and artistic expression. “A story is a story” she said, “and it must be told, no matter what medium.” She attributed gaming’s popularity to the desire of audiences to interact and be involved in a story. While there will not be a divide between gaming and film, she said, “it is important to create an ecosystem” so that artistic expression can thrive through games or film.

The first discussion featured Sean Vanaman, a designer from Camp Santo, developer of the popular indie game¸ Firewatch. This discussion focused on narrative that pulls Firewatch along. A man gets a job as a fire lookout in a national forest. It is original in that its story is pulled along by the protagonist’s relationship with his supervisor, whom he only communicates with over radio. Throughout the game the player has the ability to decide what decisions the protagonist had made in his past, and, therefore, directly affects players experiences as they continue through the story.

The next game discussed was Blizzard’s Overwatch, with its lead writer, Michael Chu. This game is an online, multiplayer game and players pick their roles from dozens of characters, called heroes. The players are divided into teams and must compete in various contests similar to king-of-the-hill or capture the flag. The game is incredibly popular among a variety of age groups. Unlike Firewatch, however, Overwatch does not have a story that pulls it along. Many of its players could get fully immersed in the games without being aware of the story at all. Chu’s responsibility, however, was to create characters and have their personalities and stories express themselves through short concise quotes and comments.

Talking about the characters in the game, Chu said there were two ways to get to know them. One, he said, was “how they feel about capturing objectives” and the other was “how they feel when they eliminate someone.” The project, Chu said, made him learn how to be really efficient because “there weren’t really too many ways to get the story out inside the game.”

Next was an interview with Kiki Wolfkill, an executive producer at 343 Industries, the game developer of Halo, which has been an immensely popular space-age shooting game, first released in 2001 on Xbox. Games like Overwatch are heavily influenced by Halo because it was the first of its kind. Wolfkill’s interview primarily focused on how to keep Halo new and interesting after a decade and a half of success.

“It’s a daily conversation,” she said, “around what are the things that are really important to the franchise and what are the things that people are just used to and not necessarily important.” She said that in sorting out these questions, she must also incorporate ever changing audiences and influences in a competitive media landscape.

After Wolfkill’s interview, Jane Rosenthal introduced the big names in the gaming industry who would be discussing how gaming compares with film. Sam Lake, the writer for Max Payne, and Neil Burger, the director of the film DIVERGENT, started the first discussion. I thought it was was an interesting starting point for artists from different backgrounds to converge. Burger views video games mainly as movies that allow the audience to control the protagonist compared to just watching them. Lake, however, was trying to express his idea that games simply are not like movies.

HIdeo Kojima

“Because it is a virtual world, then there are many layers to the story,” he said, admitting that sometimes it is okay to take control away from players to direct the story, as in a movie, but unlike movies, the virtual world of gaming “blends many different mediums.” Like in the real world, Lake said, “We listen to the radio and we watch television,” so in a virtual world, a player is allowed to do all of these things with a sort of narrator, unidentified, pulling the story along.

Following the discussion between Lake and Burger, came the event that swelled attendance unlike any other interview had. It was the interview of “Legendary game maker” Hideo Kojima by video game journalist, Geoff Keighley. Kojima spoke Japanese, and his comments were delivered through an interpreter.

Although this interview was meant to be the highlight of the festival, many in the crowd were obviously disappointed with Keighley’s line of questioning. All the interviews and conversations were centered on video games as a medium of artistic expression, and the topic of film was used as an anchor for people to base their understanding off of. However, Keighley proceeded as though it was all about film. He asked Kojima several times what films influenced him. Kojima’s said that he was not familiar with any new films but that TAXI DRIVER by Martin Scorsese was his favorite growing up and that he watched it every morning before going to high school.

Later, Keighley asked Kojima if he would ever make a film. “Definitely, one day, I would love to, but right now, it’s impossible,” he said through his interpreter. He said that he loves films so much that if he were to start making one, he would never finish because he “would always find something to fix.” The interview was disappointing because through his work and through his interviews Kojima has displayed an insightful perspective on history, art and world events. Keighley’s questions did very little to allow any of that insight for the audience that day. Fans had to be satisfied with the information that Robert De Niro was Kojima’s favorite actor and that the headband worn by his iconic character, Snake, was inspired by the headbands De Niro and Christopher Walken wore while playing Russian roulette in the film DEER HUNTER.

The final interview was the most successful in bridging the gap between filmmakers and game-makers. It was also the most entertaining. It was a discussion between the filmmaker, Doug Liman, who directed THE BOURNE IDENTITY, and Ken Levine, the creator of the Bioshock game series. The discussion evolved around the obstacles both share as artists, directors and leaders. They relayed their experiences to the audiences with anecdotes from their careers and a good amount of humor throughout.

Levine’s Bioshock is one of the earlier games to give full control to players and introduce branching narratives and alternate endings to its story. This means that many games will interrupt a player’s game play to guide them along the game’s intended path. Bioshock, however, found a way to avoid doing this, and, instead, was able to allow the player to explore a world without ever losing control of the character.

At one point of the conversation, the interviewer spoke about how the pleasure of watching a movie is about being shown a story unfold, whereas the pleasure of a game comes from having influence how the story unfolds. Levine then asked Liman if he ever wished to apply this ability for a narrative to branch out, as it does in video games, to his films.

In a rare moment of understanding displayed by a filmmaker for game production, Liman responded, saying that he thinks viewers get that experience from watching characters like Jason Bourne in a situation where he has to make a decision.

The audiences decide what they think would be the best decision. Then, finally, they witness Bourne “do something probably more clever” than the audience would do in that moment. “So,” Liman said, “you kind of have the pleasure of watching someone who’s really great play a video game.”

The Tribeca Game’s Festival was a rare opportunity for game makers to share their knowledge and experience with minds from the far more developed and widely embraced film industry. The audiences at the festival had the fortune to witness this and learn as well. The 2017 Tribeca Game’s Festival was a great success.

James Kelly can be reached at James.Kelly41@myhunter.cuny.edu

James Kelly