Pictures Courtesy www.hadleyaustin.com

DEMON MINERAL is a mesmerizing documentary about the legacy of poisonous uranium mining on the Navajo Nation, which extends into the states of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. The film reveals the savage contamination of the land by over 500 unremediate uranium mines.

DEMON MINERAL cinematography is stunning. Its imagery generates feelings like a cosmic centrifugal force pulling viewers deeper and deeper into the film with its portraiture of activists dedicated to creating a safe living space for The Nation feature as well showing the face of villains and villainous practices – as well as other powerful scenes.

The documentary by Director Hadley Austin explains the practical and spiritual reasons why Navajo people choose to stay on their land despite the radioactive perils and risks. Her film captures the invisible danger of uranium mining through the use of searing infrared black and white cinematography. Austin’s film also addresses the incredible lack of awareness and attention given to the issue compared to other nuclear disasters.

Director Austin wants to raise awareness about the ongoing uranium mining and its environmental and health impacts, and to advocate for the cessation of uranium mining and the development of a viable cleanup plan. DEMON MINERAL has a broad expanse, not only targeting a wide audience but public policy enthusiasts and those unfamiliar with the Navajo nation and uranium mining.

The cinematography massaged this reviewer’s brain, making him fell as if he was in the film in a amazing way that has happened but not in recent years. It made him aware of connections with other critical happenings occurring contemporaneously and in times past. The film, especially for those with opened minds, allows for what can best be called as a cosmic experience. Audience members may need to see DEMON MINERAL several times, not because they might have overlooked or missed important features and elements in the narrative but because it’s such a great experience and every time they watch they may move to a higher level of understanding.

DEMON MINERAL Q & A, Part 1

Edited for Style, Context & Clarification

Director Hadley Austin, Picture Courtesy www.hadleyaustin.com

Hadley Austin is a gifted filmmaker/director, producer, poet, photographer, and aerialist whose oeuvre is rooted in historical research, social justice and the natural world. She lived for a long time in a border town to the Navajo nation. The people in the film, she said in an interview with HorrorBuzz.com magazine, were her friends and friends of friends and friends of friends of friends. “Our translator is my ex-boyfriend’s mom,” she said in the interview.

Here is a link to Director Austin’s Instagram page, at least one source for those who want to keep up to date with her: Click right here.

Director Hadley Austin: So I’m making my way to Flagstaff, Arizona, which is in part where the film was made; well, just north of there. And there’s going to be a community screening in Flagstaff. And then there’s the very next day screening in Window Rock, which is the capital of the Navajo Nation, and is not terribly far from Flagstaff. And then we are going down to Tucson for a screening in Tucson.

The film’s DP (Director of Photography) is also my life partner, and then some people who are in the film are coming to some of those places, especially Flagstaff and Window Rock, because those are closer to them.

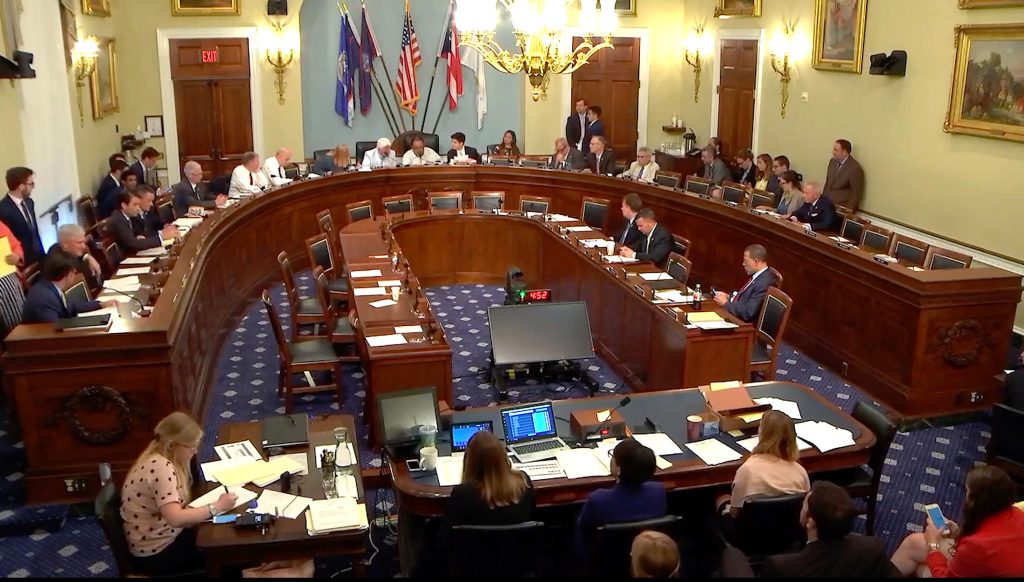

Gregg Morris: There are parts of DEADLY MINERAL that really pissed me off, particularly with those … that … one of those (U.S. Congressional) committee members. [I’m stumbling in the interview trying to recall specific details and names from documentary scenes of Congressional meetings in Washington D.C.]

Director Hadley Austin: Gosar.

[Austin is referring to Paul Anthony Gosar (/ˈɡoʊsɑːr/ GOH-sar; born November 27, 1958) an American far-far-right politician who has represented Arizona’s 9th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives since 2023 and represented Arizona’s 4th congressional district from 2013 to 2023. Gosar’s snide comments in the committee meetings in the film set off visceral chills and alarms in this reviewer because of his dismissive and facetious attitude about what many consider genocide and crimes against humanity directed against the Navaho community.]

Director Hadley Austin: Yeah, yeah. Even Winona LaDuke argued that that’s what was happening. She called it a genetic genocide. I don’t know if she said that, that might need a fact check. It is, in my estimation, an act of genetic genocide. I just don’t know if I’m borrowing that from one on LaDuke. But she did call it nuclear colonialism. That was a term she coined writing about that specific place in that specific issue.

And it’s not just there too, I mean, it’s like it’s all over: The Rockies, the Navajo Nation is a particularly acute example, and there are other examples like on indigenous land in the Congo and Saskatchewan. They [mining corporations] do tend to choose remote locations for reasons that are sort of obvious I think. And often locations where there’s a language barrier to dig these mines that have these catastrophic effects. But there are mines all up the Rockies, and I think that all things, it’s a class issue too. There’s a lot of factors, but it is the disenfranchised who suffer, most certainly.

One of several captivating images about the truth and nothing but the truth about the ravaging of Navajo communities.

Gregg Morris: How has the news media reacted to your film in the communities where’s there a screening or publicity?

Director Hadley Austin: Well, we are very small potatoes. I think that that’s an important thing to consider. This is sort of the little film that could. It’s my first film, and we got some very generous funding from the Redford Center and also from V-A-C.

But we are very low budget film. We did not have money for marketing. So I’m not surprised to say that large media has not responded to the film. We’re a film that has been in some really fabulous places, especially for a film of its size.

But I don’t know that we’re the kind of film that even would not be noticed (by major news media) because we don’t have a theatrical run,* which isn’t to say we won’t, but just that we haven’t the kind of things that get you in the New York Times, that get you reviewed in the LA Times. We haven’t had those things because we are small.

{*Theatrical runs refers to the duration of a particular production’s showing in movie theaters. Naturally, popular movies usually have longer runs compared to lesser-known and talked-about ones.}

But I’ve been interviewed often when the film has screened in places that are close to either the issue itself, like when we screened in Utah or are close to displaced populations. When we screened in the Bay Area, I have had some very nice attention from local NPR, from local media, who are commenting on the issue. And that’s been really interesting.

And it’s been really interesting to talk to media in different parts of the country about this. Because for instance, in Utah, the first two new opened, two new uranium mines, opened in southern Utah for the first time in eight years. In America, we have new uranium mining. And actually to correct myself, I think they were decommissioned mines. I think they were zombie mines (inactive modern-era mines that have not been cleaned up by responsible companies) that have been reopened, but still are still operable.

Uranium mines running for the first time in eight years. The state of Utah was very activated when I was in Salt Lake City. I got a lot of response. And for the most part, people feel the way that you are describing feeling. Some people are even surprised and they live near it. But to be honest, we haven’t had a lot of media attention outside of the screenings that we’ve done close to where the issue is.

Well, I mean, it’s certainly how we are all getting our mine information. It’s how we know it’s happening with the minds. There are people on the ground working with organizations … documenting what’s happening at the mines, and then they are posting it on Instagram, sometimes on Facebook.

I’m sure TikTok, but I’m not on TikTok because I’m an old. But yeah, I think it’s a really useful way to communicate, especially when perhaps, I don’t know if this is the case with uranium mining, I do think it is the case with other issues, but where there’s a money lobby and a vested financial interest in not making certain entities look bad. I think that this sort of on the ground reporting and using social media, I mean, we’re seeing it being immensely powerful in this way in Gaza right now, for instance.

But I think it’s really got a place in how we gather our information and come to conclusions about things. I do know, for instance, the LA Times, they publish Judy Pasternak, and she writes about this a lot. I mean, she’s been writing about this for 25 years. And so I don’t know that it’s always the case that with this particular issue, your larger media won’t touch it or something like that. But it is certainly the case with some issues.

Gregg Morris: Okay. You’re calling this, I was sort of stunned that this, I mean, this is your first film, wow. So how did you get into filmmaking? [Ten years ago she was a public school teacher in Chicago where she still lives.]

Director Hadley Austin: I love Chicago. It’s been very good to me. I love all my homes, but yeah, yeah, I taught … for about 10 years and public school teaching is a terrible job. And I needed to quit. I had to quit. I had already outlasted the average by 10 times. Literally I was ill.

I felt like I was literally dying. And around that time, about a year before Standing Rock happened, well, the most recent Standing Rock, it’s been the site of three massive protest movements in America. And I went there just to see it because I had spent my early adult years out where the film was made doing what might might’ve then been called water protection. I’ve never been much of an activist in terms of being on the street or putting myself in positions that the state might consider illegal.

That’s not my role in the project, but my role in the project has always been observation. I was always a green band person. I would stand and observe. Documentation has, also, always been my role. Education has always been my role. So anyway, I was at Standing Rock and I was thinking about how this was fascinating.

Everybody cared so much about this water and it hadn’t even been damaged yet. And I just thought if people knew about the water on the Navajo Nation, if people knew about the water issues on the Navajo Nation, then maybe they would care as much about that as they do about Standing Rock. And then what would happen? That could be really interesting. And I didn’t think that I could single-handedly make an action like that happen.

But then a couple years after that, I reached my limit with teaching on Chicago’s west side, and I met my now partner who is a cinematographer and also a filmmaker. And we just decided to make the film and we just did it. We had no funding for the first two years or so. He shot it and I did all of the other things. And then when I needed help, he’d help me in terms of, we’d both look at the applications for funding, but we did it together.

And it was something I just felt compelled to do. It was in many ways, just an impulse, a thing I did. I do have a background in poetry, I have a background in education. I think that those things actually made structuring a film and a bit second nature. I view it as an art object and an educational tool. And so I view it as an extension of the work that I’ve been doing my whole life until now, but it’s a different medium.

A Brief History About Standing Rock

In January, 2016, the Dakota Access Pipeline was unanimously approved for construction, with the aim of creating a direct route to transport crude oil from the North Dakota Bakken region through South Dakota and Iowa into Illinois. The controversial pipeline could destroy ancestral burial grounds and poison the water supply for a sovereign nation as well as millions of Americans downstream who rely on the Missouri River.}

{All eyes were on Standing Rock late last year as unwarranted armored vehicles rolled in. Law enforcement used automatic rifles, sound cannons, and concussion grenades against water protectors. An estimated 300 protesters were injured in November when police in riot gear used water cannons for hours in subfreezing weather to disperse them.}

{Personnel and equipment pouring in from over 75 law enforcement agencies from around the country and National Guard troops created a battlefield-like atmosphere at Standing Rock. Escalated police militarization was used to intimidate and silence water protectors’ free speech and their right to protest a pipeline which passes near sovereign territory.}

{Thousands from across the globe have joined in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe to stop the construction of the Dakota Access pipeline. The protest has brought together 200 or so tribes that have not united for more than 150 years.}

{President Trump took executive action on January 24, 2017 encouraging the Army Corps of Engineers to override environmental review and speed up construction of the Dakota Access. Pipeline near the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation. Any day now, law enforcement may try to disperse water protectors with unnecessary and dangerous use of force. With resilience, water protectors have already endured militarized crackdowns, police abuse, and daily intimidation – simply for defending their water rights.}

Gregg Morris: Okay. So what was the first film? Have a title that you and your partner were doing? You actually came up with this.

Director Hadley Austin: This one.

Gregg Morris: Oh! This, one.

Director Hadley Austin: This film, DEMON MINERAL. This is It.

Gregg Morris: Where on the West Side did you teach?

Director Hadley Austin: I taught at Hermosa, just north of Austin in Chicago.

Gregg Morris: {NOTE: This reviewer was impressed with the equanimity of the activists and witnesses who were not put off by the arrogance and condescension of the elected officials. They were not intimidated nor unsettled.} So I’m trying to come up with a question. The right question is how were they able to do that? I mean, there was no not one flicker of a snarl. I got pissed and then I got angry (watching the scene below).

Director Hadley Austin: Yeah. Well, two things. One, I mean, you’re absolutely right. And I often feel this way when I’m with my DNE friends and we’re in a challenging space. But one thing is that whenever I screen the film in knit communities or broadly indigenous American communities, people laugh a lot more. The film has funny moments in it that maybe aren’t funny to the uninitiated or the people who haven’t spent a lot of time in a DNE community or even in some instances broadly in reservation air quotes, to use the government term reservation communities.

But there is a kind of humor, a dark humor that I think is part of the answer to your question. I think part of how they do it is there’s a shared kind of cultural dark humor that is affirming, creates connection, allows them to laugh at the things that are horrifying.

And I also think that, so a lot of times there’s this term that’s called Indian time.* It’s not a nice term, it’s a western term … where people talk about things happening late or things happening and what is perceived to be a disorganized way or something. But I have always had a real positive regard for what people were calling Indian time.

Again, this is not a cool term, but it’s the insulting term that is used. I’ve always had a really high regard for this, because it’s thoughtfulness. What’s happening is reflexive. What’s happening is consideration. What’s happening is a pause, and it happens in everything. It happens in how the day is scheduled. It happens in choosing how you’re going to respond when ghosts are and insults you and cuts you off. It’s like how you respond to someone you don’t care for, whose actions you don’t care for. And it’s really a generosity.

{*National Public Radio Code Switch article about Indian Time, Colored People Time …}

Any situation is being given consideration before response. And that is a cultural norm in these spaces. And I think that that’s also part of how they do it. This is just accepted, this is how communication happens. It happens in this very, and if you’re not careful in those situations, if you’re not familiar with those situations, you could just assume that nobody ever wants to talk to you because they wait so long to speak after you finish speaking.

They will wait a really long time before responding to make sure you’re done to make sure that they’re saying what they want to say. And actually, our translator, Judy, another Judy, I’ve mentioned a different Judy before, but our translator, Judy Basham, came with us to one of the screenings and did one of the Q. And it was actually a question that I asked her because I was like, well, Judy, how do you feel about the structure of this film?

A really slow film? And I told her this, I feel like it moves on to use the mean Western term Indian Time. And her response was, yeah, I think it does. And the way that she characterized it was we try to consider before we say or do anything, whether it will do harm, whether it will even harm or offend the environment. We always try to pause and consider. And so I think that’s part of what you’re seeing and picking up on. And I do think it is, it is a communal strength that comes from this communal habit of doing exactly what Judy said.

Gregg Morris: Okay. Wow. Oh, okay. Slow. I mean, I think, well, the first thing, the visuals, the scenes were so stunning that it was mesmerizing. So I would think something like this is a little slow, but this is just, wow, this is just mesmerizing. And I think, I hope this makes sense in what I thought was the slowness. It was massaging my brain.

It was making me a part of the film in a way that I can’t recall being made part of a film. So eventually it just sort of vanished, that the film was slow. Instead, the film was so effective at what it was doing to my brain and my senses and making me aware and looking at connections with a whole lot of other stuff that it’s like one of those things, experiences, you got to do three or four times, which is my way of saying people need to see this four times, not because they’re going to miss anything, but because it’s such a great experience and every time you watch it, you move to a higher level of understanding, you make better connections.

Director Hadley Austin: I really appreciate that. Yeah, I wanted it to be meditative. Oh yeah, that was my goal. I wanted it to be meditative, but I wanted everyone to slow down. I wanted everyone to hang out in this slower, more reflexive, more contemplative space with more consideration in it. And I did also very much want to transport people there because the foundational thought I had was, how do you make people love something they’ve never seen? How do you make people love a place they’ve never been to? And I felt strongly that transporting them there was key. I love this place because I lived here, and if you don’t get to live there like I did, if you don’t get to be so lucky, then what will make you love it? Because I think obviously we should love everyone and everything, but that is really abstract and challenging. So we have to force trying to force your love.

End Part 1 Review, Q&A

Gregg W. Morris can be reached at gregghc@comcast.net., profgreggwmorris@gmail.com

Editor, Publisher Gregg W. Morris @ gregghc@comcast.net, profgreggwmorris@gmail.com