THE SILENCE screened at the New York Latino Film Festival August 23, and the Q&A with Director Rudy Valdez and Moderator Calixto Chinchilla, Founder/Executive Director of the festival, was riveting. Film reviews of THE SILENCE are embargoed until October 15 when it debuts on HBO – no embargo for this Q&A article.

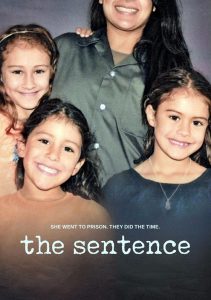

The documentary won the 2018 Sundance Audience Award. Valdez explores the devastating consequences of mass incarceration and mandatory minimum drug sentencing by telling the story of Cindy Shank, his sister, a mother of three young girls as well as their families and relatives – and his experiences. The film was 10 years in the making.

Cindy Shank was sentenced to 15 years by a federal judge for her tangential involvement in a Michigan drug ring years. Regarding her tangentiality, she was the girlfriend of a Lansing Michigan drug dealer who ran his business out of their home. Though she was not directly involved in the criminal activity, she was there when things went down. She didn’t drop a dime on him, never turned him in. She eventually left him and started raising a family with her new husband and things were going well until the feds knocked on their door several years later.

At the NYLFF Q&A, Valdez talked about the 10 years of his up front and personal, imaginatively creative, fly-on-the-wall documentation of the literally day-to-day life of his mom and dad and other relatives, as well as Cindy’s three young daughters and her husband living in the wake of her incarceration as they seek her freedom. This is reality filmmaking at its best.

The Q&A has been edited for style and length.

Part 2

The recipient of mandatory minimum sentencing laws, established in the 1980s during the Reagan Era, Cindy Shank was charged with her late boyfriend’s crimes, in what came to be known among criminal justice advocates as “the girlfriend problem.” Despite being a first-time offender with a spotless record, Shank was sent to prison weeks after giving birth, leaving her newborn infant and two additional children in the care of her husband, Adam, and her parents and siblings in Lansing.

Drawing from hundreds of hours of footage, filmmaker Rudy Valdez shows the aftermath of his sister Cindy’s 15-year sentence for conspiracy charges related to crimes committed by her deceased ex-boyfriend. In the midst of this nightmare, Valdez finds his voice as both a filmmaker and activist, and he and his family fight for Cindy’s release during the last months of the Obama administration’s clemency initiative.

NYLFF Founder and Executive Director Calixto Chinchilla: “Were you shocked to learn that the girlhood experience was far more deeper than you thought?”

Valdez, “Yeah, definitely. When Cindy first went away, I went home and I literally thought that it was a clerical error,” Valdez responded. “I thought somebody forgot to carry the 1 and she wasn’t supposed to be in there. I started doing research, and I started calling people and calling organizations, and I quickly realized that not only is she supposed to be in there. Not only is this happening …

Calixto Chinchilla, “… This is throughout the country.”

Valdez, “There are thousands of people. Cindy’s story is not unique. That’s the crazy thing. It’s just as bad on a state level, as well. This is a problem that’s happening in our country to thousands and thousands of people. Men, women, most importantly the families and children left behind. It’s a huge problem.

Calixto Chinchilla, “Has their been any talks of reform.”

Valdez:

“There was certainly a lot of movement in this movement during the Obama administration. There were a lot of safety laws put in place and a lot of … put forward that have, with the current administration, been stripped away and taken away. I don’t know if people notice this or not, but one of my things in this film is that I tried to make it as apolitical as possible.”

“There’s no going into the history of how this started, who’s perpetuating and all of those things. And that’s on purpose. It’s because I honestly don’t care who fixes this problem. Anybody who wants to fix it can fix it. There are other films that go into depth about how these laws are put into place and that entire process. I felt like that wasn’t going to be my strongest film. My strongest film was going to be to put a face on this problem.”

“I wanted people to feel this loss. I wanted people to feel this time. And I wanted them to feel like they were a part of the family. Everything in this film is on purpose, from the lens choice that I used for most of this film. I shot most of it on the 50 1.2 completely wide open. I don’t know if anybody knows what that means: It means that if I’m looking at you, I see you. Everything falls away.”

“I wanted you to be a part of my family. I didn’t want you to watch my family. I didn’t want you to feel like you were getting a sneak peek into what’s happening. I wanted you to be in that. That’s why I never mic’ed people in very tense scenes, because I didn’t wanna rely on stepping back and getting somebody’s audio.”

“If I was talking to somebody, I needed to be this close. There’s that scene where Cindy calls and there’s 13 people in the room, and the phone gets handed around. Every time somebody had a turn to talk with her, everything else falls away because the only thing that mattered in that moment was her connection she was having with that person. And I wanted you to feel that. That’s why, that scene when my mother is talking about the moon and she’s saying, ‘I watch the moon because I know Cindy does.’ And then she turns to me and she says, ‘I’m going to put your laundry away.'”

“I left that in on purpose because I needed you to know who was holding that camera. That you were in that room with my mother. You were me. You were my eyes. You were experiencing this with us. It’s all on purpose. I needed you to be there with me because that’s the only way we are going to change.”

“Voting is going to change this, voting is going to help this, but I think we need a cultural shift in our country. We need to be able to put ourselves in other people’s shoes and understand what’s going on and the true loss that’s happened.”

Calixto Chinchilla, “This is a unique situation because it’s not like you researched this before. This is real life. Did you ever take the time to research how this law may be affecting other Latinos and People of Color? You didn’t put any thought into any of that other stuff. Was there a moment that you said ‘I wanna do some real research as to how this law is affecting communities of color’? Did you do that post?”

Valdez:

“No, I did that during. There’s a whole layer of this film that was stripped away, and it was my fight. My fight for Cindy. I completely took it out because A, it was the only time aesthetically that I wasn’t holding the camera, and it felt really disjointed from the personal story that I was trying to tell. And B, I certainly didn’t wanna try and make it a Rudy-is-such-a-cool-hero-brother-guy film.”

“But over the course of the decade, I became an advocate. I became somebody who, anytime there was a hearing going on in D.C., anytime there was an opportunity to speak, somebody would call me and say, ‘Rudy, in a few hours, they’re having a hearing. They’re having a protest. They’re having something.’ I would jump in my car and I would drive there, and I would speak to every single person there.”

“I would speak anytime they would let me speak. I would speak every time they wouldn’t let me speak. I would talk to anybody who would open the door. I would open a window if they wouldn’t open a door, and I spoke. And I spoke and I spoke and I said Cindy’s name, Cynthia Shank. And I became an advocate, I became a fighter not only for Cindy, but for other people.”

Calixto Chinchilla, “What type of people are they, especially in this boat?”

Valdez, “It’s tough, because again, Cindy’s story is not unique. There are other people out there. You’re like a needle in a haystack. Every time you go to one of these things, there are so many people that are fighting for their loved ones. There are so many stories like this. We were fortunate enough to have it captured on film, but there are so many people who are going through this. I need this to differentiate myself.”

Calixto Chinchilla, “We realized because when we first announced that the film was playing here, on our Facebook we actually got hit by a couple of prison reform organizations that hope their former inmates can become the face of the issues. Take us to that moment where you showed this to your nieces for the first time. Your sister for the first time. What was that moment?”

Valdez, “I kept this from everyone until right before … we premiered at Sundance in January … right before Christmas. I gathered my family in the theater back in Michigan, and I said, ‘Look, I just filmed the worst decade of our life. I cut it down to a manageable 85 minutes. I color corrected it. I put a beautiful score under it. Here you go.'”

“I sort of walked out of the room and I didn’t know what they were going to take. But I will tell you this. When we found out we got into Sundance, I called my parents and I told them. I told my dad, and he was like, ‘Oh, I see. That’s so nice.’ He doesn’t really know what I do for a living.”

Calixto Chinchilla, “My mom’s the same way.”

Valdez:

“I called my mom, and she literally was like, ‘Oh, mijo, that’s so great. Can we do it in New York, I love New York.”

“My sister Cindy called my dad and sort of explained to him what it meant, for a guy and a camera for nine and a half years to tell a story that’s a one in a million story. Take it o Sundance, which is a one in a – I don’t know what the chances are – to be in a competition, all these things. My dad called and he was crying. And all he kept saying was, ‘How did you know? How did you know this was going to happen?'”

“And I said to him, ‘Dad, I didn’t know. I didn’t know Cindy was going to get clemency. I didn’t know this film was ever going to get finished. I didn’t know we were going to get into Sundance. I didn’t know we were going to … I didn’t know any of these things.'”

“I said, ‘What I did know was that we were about to go through something that was going to test us to our limits, and that we as a family were going to handle it with poise and grace, and we were going to make it through. And we were going to be very proud of it. And I wanted to capture that.”

Calixto Chinchilla, “The thing that really hit me is the little one, because she’s literally seeing herself grow up, and she’s seeing this again. Older. What was their reaction like?”

Valdez:

“It’s interesting because her especially … she just … I was actually watching her while she watched it, and every time she came on screen she was like … and she’s seen it a couple times, and every time she’s like ‘That’s me.”

“I think that, again, much like the ramifications aren’t going to be seen for five or 10 years, I hope and I pray that as they’re going through some of these things, as they’re turning into young adults and going into adulthood, that this is going to be something that they can look back on as they’re dealing with these issues of possible abandonment or other things.”

“They can look back on this time capsule of their life and understand that they were loved. They were cared for, they were the center of this universe: Number one, that they did nothing wrong. I think that’s something that they’re going to struggle with when they look back at this. Maybe they thought it was something that they did that took their mother away, or maybe it was something that their mother did or wanted to be away.”

I need them to understand that they were loved and it wasn’t their fault. Hopefully that will help with the healing and help with the long term effects that this is going to have on them.”

Calixto Chinchilla, “You hear every conversation, every phone call, everything.”

Valdez, “There’s so much. There’s a super-cut that I’m putting together just for Cindy and the girls that is them growing up together. Growing up without a mom.”

Calixto Chinchilla,“We’ll take a couple of questions from the audience, but what do you feel is the biggest takeaway in the film? When you’re given clemency? Is that a total wipe out?”

Valdez, “Clemency … what Cindy was given was actually commutation. What it technically is is like a re-sentencing. If you were to be sentenced right now and this is what we think you would get, and basically, they took out all the other factors and said time served. You’ve done enough time and you can go home. So she’s not innocent, she’s guilty. It’s on her record. She’s a felon. She still has probation for another five years. There’s still a lot of hoops she needs to go through.'”

Calixto Chinchilla, “So, even in the work, she still has to indicate …”

Valdez, “Yeah, and she told me when she went looking for jobs. Every interview, the first thing she said when she sat down was ‘I’m a felon. I’m looking for my second chance. You’re not going to regret it if you give me one.’ That was the first thing she said at every interview. Every single interview, she went on, she was offered a job. Every one.”

Calixto Chinchilla, “That’s the hardest thing is the prejudice. Sometimes employers, you’re not supposed to do that. Sometimes you don’t know the backstory. The guilty are sometimes the innocent.”

Valdez,

“There are so many layers (to this film). I could talk for hours about this film because there are so many things that I purposely put in this that … one of the things we need to do is change the lens of what an incarcerated person is. What a family of an incarcerated person is. When you hear about it, you think of somebody who you don’t want to live next to, who you don’t want to sit next to.”

Picture courtesy of NYLFF

“There are a lot of really wonderful, amazing people who made a mistake. They deserve a second chance. This is a country of second chances. There are so many people out there not getting them. And that’s because people have this assumption and they hear this rhetoric about being soft on crime and letting people out, and it’s terrible. We’re hearing it right now. As we talk about people not wanting to do away with mandatory minimum sentencing or this problem with mass incarceration.”

“They’re saying we need to double down and we need to incarcerate harder. We need to do all these things because these people are murderers and rapists and all of these things. No. Not all of them are. Many people deserve a second chance. Cindy is an example of that, and she’s one of thousands. We need to change how we feel about this. And if you don’t care, one of the hidden layers in this, and I always try to give this out in Q and A’s, is … if somebody watches this and they come at it from a cynical point of view and they don’t care about Cindy. They don’t care about the girls, they’re not touched emotionally by anything, that’s completely fine.”

“One thing you cannot deny is that Cindy is not a detriment to society. Nobody should fear her, and she deserves a second chance. You cannot deny that.”

Gregg W. Morris can be reached at gmorris@hunter.cuny.edu